Does the 10 year longstop still apply?

Not so long ago, in our Communique article “How long to keep records” we said

“The warm fuzzies induced by the 10 year longstop on liability under the Building Act have been under threat from cases brought to Court. So far, so good. But it would be unwise to biff out everything related to a project as soon as the longstop is reached”

Alas, in May 2021 the decision on the October 2020 hearing of BNZ Branch Properties Limited v Wellington City Council [2021] NZHC 1058 has made good on that threat. There may be the possibility of an Appeal, but currently, the position is that if (for example) the owner makes a claim on the contractor at 9 years and 364 days, that contractor would have another two years to seek a contribution from you as a “third party”.

The case arises out of the BNZ building on the waterfront in Wellington, which was damaged in the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake and later demolished.

In August 2019, BNZ sued the Wellington City Council for negligence in respect of granting the building consent, inspecting during construction, and issuing a CCC. A month later, Council sued the engineers, Beca, as a negligent third party, seeking a contribution in accordance with s17 of the Law Reform Act. Beca argued that it had provided its engineering services in March 2008, more than 10 years before Council filed its claim, and thus the claim was time-barred by s393(2) of the Building Act.

The issue before the court was not whether or not Beca was negligent, but whether – in consideration of the limitation issues – they were liable.

The Building Act s393(2) states

“….no relief may be granted in respect of civil proceedings relating to building work if those proceedings are brought against a person after 10 years or more from the date of the act or omission on which the proceedings are based.”

In simplistic terms, the understanding has been that you are not liable for your actions (as a building designer) beyond 10 years from the date on which your actions may have given rise to the alleged problems.

NZ case law has confirmed that in respect of primary claims between plaintiffs and defendants; but the position has not been so clear in relation to third party claims. This was a test case for that issue, with about $100 million at stake.

Beca argued that the use of the words “civil proceeding” in s393(2) of the Building Act was intended to include “every form of civil proceeding regardless of its source or makeup”.

The High Court, after a detailed consideration of the relationship between s393 of the Building Act, s17 of the Law Reform Act, and s34 of the Limitation Act 2010, held that the term “civil proceeding” in s393 of the Building Act refers only to a primary claim between a plaintiff and defendant, and does not include a claim for contribution.

Third party claims – such as the Council’s claim against Beca – must be initiated within a two-year period provided for in the Limitation Act 2010. This judgement establishes that so long as a claim is made on a party within the Building Act 10 year longstop, that party would then have two years in which to make a claim against third parties.

NZACS has previously suggested that the WHRS timelines justify keeping your documents 12 years, not just 10: such things may (almost) be in the past, but this new case reinstates that recommendation. Those “warm fuzzies” are now facing the reality of winter.

Climate change and Natural Disasters

Recent natural disasters

Those of you who have been caught up in Cyclone Gabrielle and the preceding Auckland rains have had a tough time, and we hope that things come right in due course. NZACS will respond where we can to reduce ongoing risks to your practice, and the NZIA has recently published some guidance to information to aid the road to recovery. For our non-NZIA members, and for those of you that may be involved in remediation or salvage of damaged buildings, MBIE has some resources at https://www.building.govt.nz/managing-buildings/managing-buildings-in-an-emergency/north-island-severe-weather-events-2023/ as does CHASNZ at https://www.chasnz.org/articles/auckland-flood-remediation-how-to-keep-healthy-and-safe-while-working-on-flood-damaged-property

In some respects these recent events may lead to similar outcomes and responses as Covid: disruption to supply chains, labour availability, and site progress. In addition, some sites will be physically affected by flooding or landslip. Inevitably, some of those who suffer loss will be looking around to recover uninsured losses: you should be thinking about whether you or a project you are working on is a potential target, and if so, what you need to do about it.

Your staff losses and family disruption need to be addressed directly: see, for example, at https://www.employers.co.nz/natural-disasters-who-pays-blog.aspx and at the MBIE site https://www.business.govt.nz/risks-and-operations/extreme-weather-information-for-business/

Personal or staff stress and losses may affect productivity, and to the extent this affects your projects, you should advise stakeholders at the earliest opportunity, so that mitigation can be managed. Focussing on your personal and business well-being is likely to be more important in the immediate future than meeting (perhaps arbitrary) deadlines.

Climate change as a design input

When advising clients on site developments, in addition to compliance requirements there is a duty of care to apply your experience skills and knowledge as a professional person. Where is it apparent that a site may be more than usually affected by climate change, higher rainfall, higher temperatures, stronger winds, flooding, landslip or off-site adverse events, these are issues to be raised with the client. This may in turn require attendances by other consultants. Pro-actively educating your clients on the potential risks is a better course of action than having to defend your position later. The records you have kept of those discussions and the resulting decisions will be an important defence if a later related claim arises.

Certification of completion

NZACS members are often asked for a certificate, when this was never intended or provided for within the AAS. Often it is in relation to whether or not the works are suitable for occupation to facilitate bank funding, or it may be a request from a Project Manager to cover off their role in the project.

The architect would be justified in seeking additional remuneration for this additional architectural service.

Such certification carries an additional litigation risk, and the architect is entitled to factor in this risk and cost when assessing fees either at the outset, or as a variation to the agreed services.

Where the Project Manager has been appointed after the architect was appointed, the architect should not be required to be put in the position of having to be the “underwriter” or backstop for the Project Manager’s responsibilities.

NZIA has recently published Practice Note 1.227 “Clause Options, Certificates and Statements”. If you are faced with having to provide a certificate or statement, we recommend that you read and use that Practice Note in conjunction with the comments above.

Pro-bono work and PJs

Pro-bono jobs are done without a fee. Or perhaps at some concessional fee such as meeting basic costs but not time and labour. Do not assume that because you are gifting your skills and resources, those that might make a claim against you will take an equally charitable approach. Your responsibilities are the same, and the other risks remain the same, regardless of whether fees are paid or not.

“PJs” (private jobs) are a time-honoured way that employees widen their experience or carry out work for friends and family. An employee acting in the “normal course of their employment” would generally be protected by the employer’s PI cover: that would exclude PJs. An employee doing work on their own account will be carrying the risk, and it is up to them whether they are insured or not.

But the problem is that in the event of a claim, the employer – even if unaware of the project – is likely to be in the claimant’s cross-hairs. Employers should deal with these matters in their staff terms of engagement. Written consent of the directors should be a precondition for staff to engage in related business interests, and all subsequent arrangements should be in writing: a congenial/collegial chat is not sufficient.

The employer, if allowing staff to carry out PJs, should:

Remind such staff of the risks of carrying out professional work without the protection of insurance; and of the necessity to meet the requirements of the NZRAB Code of Ethics.

Insist that the client is made aware that the practice is not involved in the project – perhaps by drafting a letter to the client – and should keep a written copy of that communication.

Make clear that there must be no use of office reputation and/or intellectual property, materials, addresses, details, resources, staff, or management.

Confirm that using your firm in any way comes as a cost to the firm which could either be classed as stealing or employee benefit, as may be agreed (or not).

Watch out for watermarks on prints, email signatures, digital files, timesheet records, etc..

Require that any and all communications in respect of the project should be through a job-specific email address, and not refer to or be recorded in or be part of the office system.

The better course of action may be to encourage the employee to bring the project into the office, along with whatever arrangements might be required in respect of fee-sharing or rewards, including the level of responsibility within the firm for that job. The firm still needs to take care in monitoring actions and communications between employee and client: there is the likelihood some will be “informal” and outside usual office circumstances.

RISK MANAGEMENT

Legal Issues & Risk Management

RISK MANAGEMENT

Legal Issues & Risk Management

CONTENTS: This Webinar (September 2022)

LEGAL AND QUASI-LEGAL ISSUES

Negligence

Duty of care in contract

Unlimited exposure to domestic claims

Duty of care in tort

Limitation defences

Joint & several liability

Copyright

NZRAB complaints procedures

Negligence

Failure to exercise reasonable skill, care and diligence.

Doing what others in similar circumstances would not have done.

Failure to do what others in similar circumstances would have done.

Negligence test

- Was a duty of care owed to the claimant?

- Was that duty breached?

- Did the claimant suffer a loss

- Was the loss caused by the defendant?

- Was the loss reasonably foreseeable?

All questions must be answered YES for claim to be established

Defences available

- If one of the above five questions is answered NO

- The claim is contractually barred (time or money)

- The claim is statute barred (time limitation, etc)

- The claimant contributed to the loss.

Duty of care in contract (1)

- Described in the contract:

hence importance of having written engagement terms

and having them signed and returned by the client!

- Described in the Building Act s14D (responsibilities of designer) Responsible for ensuring that plans and specifications or advice (if followed) will result in compliance

- Domestic projects: described in the Consumer Guarantees Act:

done with a reasonable level of skill and care

fit for the purpose you and the customer agreed on

cost a reasonable amount, if a price wasn’t agreed beforehand

completed in reasonable time, if timeframe wasn’t set before.

Duty of care in contract (2)

- Domestic/Residential projects:

Under Consumer Guarantees Act, a $ limitation cap included in the terms of engagement (i.e. contract for service) for a residential project will be of no effect: the liability cannot be capped.

In relation to residential contracts, the minimum/default building contract terms are set out in s6 of the Building (Residential Consumer Rights and Remedies) Regulations 2014, but under s362B of the Building Act, these do NOT apply to design.

Duty of care in tort

A tort arises when a party owing a duty of care to others breaches that obligation, and that breach results in a loss (or “damage”) to those others. Scope is established by case law, not (generally) by legislation

To whom do you owe a duty of care in tort?

It depends! Basically, anyone who might foreseeably be affected by your actions

When does a duty of care arise?

It depends! But if you are involved in your professional capacity, you are expected to have regard for the interests of those affected by your actions, to the extent that others in your profession would, if placed in a similar situation.

Duty of care in tort – Examples

Example 1 – Concurrent claim in contract and in tort: The architect designs a defective building, which the client on-sells to others. The new owners could bring a claim for damages against the client in contract (pre-sale representations) and against the architect in tort (duty of care to owners/users of the building). The client could bring a claim against the architect in contract (design/observation failures), and in tort (duty of care extended beyond contract to include owners/users of the building).

Example 2 – Duty to Warn: An LBP Carpenter was working as an employee for the non-LBP building contractor who was “cutting corners” in a house weathertight remediation project. The LBP Board decided that the LBP had a duty to inform the owner that some of that work was inadequate or defective. The Board had regard to the significance and potential outcomes arising out of the defective work.

Example 3 – The Disappearing Developer: Apartments and townhouses have been the source of numerous NZACS claims. It is not unusual for the developer to be unable to fulfil a later claim by the new owners. The architects or designers (and the Council) are routinely called upon to make up the shortfall, on the basis that they owed a duty of care to the purchasers.

Joint and Several Tort Liability

The Claimant:

- may seek full recovery from each or any parties that contributed to the damages.

- is not (usually) concerned about who pays (if anything) to make up settlement sum.

- cannot claim more than their actual loss, nor for any loss caused by their own negligence.

The Designer/Defendant:

- is liable to the extent that they contributed to the damages.

- is potentially 100% liable for the damages arising out of the design defects.

- if not engaged for site observation, will not be liable for construction defects

- if engaged for site observation, will be liable for the damages which arose as a result of their failure to observe, and take action

Joint and Several Tort Liability – Examples

Example 1 – Insolvency: In a leaky building claim, all the defects were the result of poor construction. The Council had signed off CCC. During remediation, it became clear that the original building inspector should have picked up the defective work. The owner sued all and sundry, but only the Council had the funds available to meet any settlement. The ratepayers paid for all of the remediation.

Example 2 – Inadequate detailing: Similar scenario, but the builder was still in business and had meagre assets. The designer had nothing to do with appointing the builder or attending to the construction phase of the project. But the designer had failed to detail a critical junction, and the builder’s solution was the reason for the leaks. Settlement was proportional: 15% builder, 15% designer, 70% Council.

Example 3 – Contributory Negligence: The designer had detailed the relationship between the garage door jambs and the strip drain across the garage door intended to catch surface water flowing down the drive. Damage was caused because that detail was not followed on site. But photos showed that the owners had failed to dispose of fallen leaves and failed to clear the strip drain, with the result that the same flooding and damage would have occurred regardless of the builder’s faults. Remediation costs were apportioned accordingly.

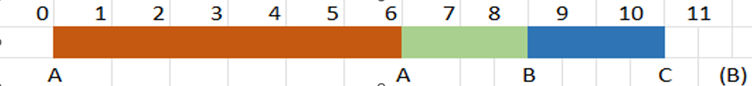

Limitation Defense (1):

In relation to “building work” claims:

- usual liability is 6 years from the time the work done (diagram = “A”)

- possibility of a 3 year “late knowledge” extension. (diagram = “B”)

- 10 year longstop is provided by the Building Act (diagram = “C”)

Limitation Defense (2):

In contract:

Legal proceedings related to a breach of contract cannot commence after 6 years from the date of the act of omission.

Shorter limitation periods may be contractually agreed, but insurance cover will not respond to claims with a contractual limitation period beyond the statutory 6 years.

In tort:

Legal proceedings cannot commence after 3 years from when the facts giving rise to the claim were known or ought reasonably to have been known.

Copyright

- Generally, the person who commissions a work owns the copyright.

- NZIA AAS terms reverse that: the architect owns the copyright, and the client has the right to use the design for the purpose intended by the engagement agreement.

- If you don’t have a signed AAS agreement, you may not be able to assert copyright.

Copyright: Examples

- AAS not signed: Architects had a specific agreement with clients which included terms that their project was to be unique. The AAS was part of the agreed terms, but it was never signed. The clients brought a copyright claim on the basis that their design was later used elsewhere.

- Copyright assigned? A project was designed by a director of a firm, who then left, taking the construction phase of the project with him. A dispute arose over whether the copyright in the design was also transferred.

- Product replication: A firm issued tenderers with a photo of a furniture item they required to be included in the priced contract. The furniture designer claimed on the basis that they alone were to be the only possible suppliers of that item.

NZRAB Complaints

The test is negligence, NOT gross negligence. This may be a low bar, and the complaint may proceed ahead of other dispute processes which might have confirmed the facts, circumstances and contract responsibilities. It costs a client very little to complain, but involves a LOT or effort and angst to defend.

BEWARE!

NZRAB Complaints – Examples

Example 1 – Testing the evidence: The architect advised the client that alterations to their cross-lease property would require approval of the neighbours. That did not happen. The client held the architect liable for the resulting problems and the architect conceded in the hope of avoiding punitive costs of the NZRAB process. When the case was properly tested in preparation for a Court hearing, it became apparent that the complainant’s assertions would have failed.

Example 2 – Leverage: The architect designed two townhouses for the client: one for profit and one for occupation. The client’s expectations did not match the commercial realities and they sought to cut their losses by seeking recovery from the architect on the grounds of poor performance. Their chosen route was to lodge an NZRAB complaint (at minimal cost) as a prelude to court action and/or to gain concessions that might make court action unnecessary.

Example 3 – Having your own cake and eating it too: The clients engaged the architect for design/observation/contract administration. The documentation was done accordingly. The clients then sought to cut costs by curtailing the construction-stage attendances of the architect. This resulted in unresolved detailing, uncoordinated variations, cost escalations and intermittent site visits by the architect. The NZRAB complaint was partly initiated because the architect declined to issue a practical completion certificate.

RISK MANAGEMENT -The Key Risks

CONTENTS:

5 KEY RISKS

Communication

Information

Performance

Money

Partial Services

PROFESSIONAL INDEMNITY INSURANCE

NZACS CLAIMS EXAMPLES

Communication

Engagement terms & scope of work

Changes to design brief – consequences

Objectives: Client, Architect, Consultant, Contractor

Information

Site and site controls; covenants, cross-leases

Client & contractor history, priorities, expectations

Performance

Yours: design, observation, administration, estimates

Consultants: skills & resources, timing, communication

Contractors: attitude, capacity, timing, communication

Materials: limitations, junctions, costs, warranties, moisture

Project Manager: passing the buck?

Money

Budgets and estimates

Variations, monetary allowances, unknowns

Payments versus progress and performance

Contractor insolvency

Fees disputes & lack of goodwill or empathy

Partial Services

Documentation versus site requirements

Inability to pick up issues or control outcomes

Loss of relationship with project and client

Defence of claims without first-hand knowledge

PROFESSIONAL INDEMNITY INSURANCE

- Responds only to risks arising out of the normal course of business

- Does not respond to contracted risks beyond those normally accepted

- Long tail (tale!): Liability may not be quantified until years later

- “Claims Made” basis: Policy must be current when events which give rise to a claim first become known to the insured.

- Policy holder has a duty to notify as soon as circumstances are known

- Policy holder has a duty to assist in the resolution of the claim

NZACS

- A co-operative run by and for architects, with group purchasing power and ability to influence PI policy terms.

- In operation 50 years, now covers 70% or more of architecture firms + some designers

- Claims Committee is available to assist members with actual or potential claims, and to provide architectural experience to their resolution by the insurers.

- Publishes Communique – advice and guidance in Risk Management

- Website resources at www.nzacs.co.nz

NZACS CLAIM EXAMPLES:

Communication

- Architect appointed to major upgrade/refurbishment project spanning several years, multiple revisions of design brief by a changing client management team: design required to evolve with aspects of the work uncovered during construction. Project manager appointed after site operations started: later multiple problems because context and responsibilities changed and not reliably documented by the parties. When it comes to a claim, what is in writing is what counts!

- Architect sends terms of engagement and fees proposal to client; client instructs the work to proceed (either directly, or by actions in continuing to review and comment on the design) but never actually signs and returns the service contract, or continues to debate its terms. Architect proceeds in good faith. Project terminated because: (a) the designs are never going to meet expectations or (b) getting the required resource consent is too hard or (c) costs are running ahead of budget or (d) divorce is pending or (e) commercial reasons do not support the investment or (f) anything else! Client then says fees are not payable because the contract either was never signed or because the architect had failed to perform; architect discovers that copyright may be unenforceable because the contract was not signed; architect discovers that the interest provisions on unpaid fees may also be voided.

- A “novel” design feature fails. Architect digs out several emails to prove that the client was fully aware of the risks and chose to proceed with the design feature. Client digs out just as many (and perhaps some of the same) emails to prove that they were “talked into” the design feature by the architect. It is unclear who actually made the decision and on what grounds, but the client’s view prevails on the basis that they relied on the architect’s advice, and the architect had the professional duty to make prudent design decisions.

- In housing work, the maximum stress level is reached when the construction is almost complete, the client can only see the defects and uncompleted work; they are stressed out by the endless decisions and costs; the builder is already overdue and being pressured to start the next project: the dream is now reality and it may not be perfect.

- Be aware that if you “recommend” a builder, the client may think they can hold you responsible for their performance.

- If you elevate your concept of priorities over those of your client, there is a risk it may backfire. Examples: The design featured the architect’s selection of views, but when the clients went on site during construction they discovered that their requirement for expansive views had been ignored. Another where the architect “expanded” the client’s design brief (and budget) to include work not asked for. Many cases where the architect’s idea of aesthetics has not matched the client’s availability of money

Information

Exceeding building height:

- Can be especially contentious in domestic circumstances where neighbours may be concerned about the effects of new work on their sun/views/values.

- House alteration designed to maximum height envelope: existing construction required the overall height to be slightly raised above expectations. Neighbour complained, and the framing had to be removed and the new top floor redesigned.

- Misunderstanding about the position of the boundary, and therefore the height control planes: was the actual boundary at the bottom or the top of a change in level or retaining wall near the boundary? A similar case where there was a misunderstanding about the boundaries in relation to an adjacent accessway: which side of the accessway generated the height planes?

- Commercial premises designed to the maximum envelope but the height controls were then exceeded by services installations designed by others.

Site Services

- Development of residential rear site required drainage to be run through the neighbour’s property. Client on good terms with the neighbour and instructed the design to proceed. Neighbour later refused to give consent, and the client claimed on the architect (and refused fee payment) on the basis that the project had to be abandoned.

- Building project required piles in vicinity of known subgrade services. Services plotted and test bores sunk. Despite best endeavours the piles or test bores unexpectedly encountered the services either not where they were understood to be, and/or whose existence was unknown. Examples include: shutting down an area of city electrical supply; filling a substantial sewer with pumped concrete; puncturing a water main; breaking up a major stormwater pipe; structural redesign to bridge over services or reposition bearing structure.

Site levels/boundaries/covenants

- No clear datum for floor levels shown on the drawings, but lid levels of manholes and sumps shown. House slab level clearly shown, and adjacent retaining walls were dimensioned but the level at their base was not. Builder built the retaining walls to required dimension and then set out the house from the derived height: house floor 250mm too high.

- Rural house designed to specific slab level and submitted for building consent. Council required increased slab level approx. 300mm above surface water flow path. House framed up to roof level and council pre-clad inspector noted that the builder had set out the slab level from priced drawings instead of the consented drawings.

- Site is subject to both local body setbacks and covenants recorded on the title or terms of sale. Examples: Architect assumes (or decides) that one or other of the controls either supercedes the other or is not required to be complied with: this results in a major redesign and damages paid to affected parties. Others where the architect advised the clients to gain the approval of neighbours but proceeded without confirming that the necessary approvals had been given and recorded in writing.

Performance

Engineering consultants

- Confusion about who is to detail/specify foundation waterproofing or grades versus floor levels.

- Engineers being overly specific about scope of work, leaving gaps (in observation particularly) that the architect is not aware of. Example – termination of foundation tanking at ground level not protected or perhaps allows water to enter behind it.

- Survey/geotech input which does not go far enough out from the immediate area of work. Examples: survey stopped at boundary, so the architect was unaware that the overland flow path was restricted = bottom floor of house built in a puddle; another where engineered fill under a house washed out because of flowing subsurface water.

- Conversely/similarly, engineer is required to observe as part of BC requirements, but architect is not: engineer fails to spot/report architectural issues which might appear self-evident, and architect gets lumbered with the outcome. Example: foundations boxed up and reinforcing placed and inspected by the engineer, but an error in the setout in relation to an existing building or boundaries is not picked up and is blamed on the architect’s drawings.

- Structural detailing (or approval of shop drawings) which requires a change to the architectural detailing, or which compromises acoustic design or vapour barriers, or creates thermal bridging, but which is not made apparent to the architect.

- Services engineers – typically works not performing to required standard, or corrosion problems – swimming pools especially!

- Late delivery/changes of structural work which then requires downstream alteration of other design work.

- Errors in calculations of lintel deflection, cantilevered slabs, wind loads, capacity of existing structural work to carry proposed new work.

Tolerances and detailing

- Inadequate allowance for lintel deflection in the pursuit of minimal detailing: large sliding windows couldn’t.

- Joinery using solid timber sections as panelling did not sufficiently accommodate timber shrinkage/warp/movement. (Similarly, veneered MDF joinery panels with one “feature” side and another thinner laminate on the reverse which warped accordingly).

- Concrete structural items designed on the assumption that specified cement or reinforcing would be used, or end-seating as designed would be provided; failure occurred because there was insufficient on-site monitoring and/or inferior products were substituted by the contractor.

- Technical issues with special places or spaces that require special attention: Indoor pools and gyms; coastal or geothermal environments; localised wind or weather conditions; animal accommodation; laboratory pressure differentials; acoustic separation or isolation; wet area tiling and associated balustrade installations; inbuilt fireplaces; concealed gutters and low-pitch roofs; materials or details which require secondary protection; exposed polished concrete floors; concealed spaces subject to potential condensation or cold bridging; remediation/recladding or leaky buildings; flooring slip hazards, plus many more!!!!

Money

Cost estimation

- House client instructs design work to proceed on the basis of a prospective contractor’s guesstimate based on concept drawings. Final design costs considerably more and the previous contractor refuses to become involved: architect accused of embellishing the work and adding costs.

- Very expensive house; client expands the budget significantly, but the cost of the final design as tendered is still well above that: client abandons the project and seeks refund of architect’s fees as well as other abortive costs.

- Client for 4 or 5 townhouses pushed the development options and cost-savings to the extreme and eventually could not achieve what they sought, at which time they lodged a claim in NZRAB as a prelude to a civil claim on the basis that they lost money and potential development profit.

Certification & payments

- Client maxes out the funding approvals, and the funders require a fixed cost price without contingencies. Site or existing building throws up issues which are clearly a contingency item: cost cutting must be applied elsewhere to free up the necessary funds. Examples: On opening up the ceiling in alteration works it is discovered that services and/or structure is unexpectedly present/absent/failed/redundant. Another where the contractor’s tender was based on using a mobile crane but unforeseen circumstances made that impossible, and extra cost was incurred because a tower crane had to be used.

Client refuses to accept Variations.

- Examples: Retaining structures requiring to be “beefed up” and/or extended in scope to deal with ground conditions which only became known when excavation done. Others where the architect has had second thoughts about a better design during the course of construction, and the contractor provides minimal credit for deleted work and maximum cost for the new design.

The death spiral of Slow Payers:

- The client thinks the contractor has overcharged; the contractor cannot fully pay his subbies; the subbies prefer to work on other sites where they are getting properly paid; there are resulting problems in co-ordinating work on site; the contract period stretches out; the client thinks the contractor might abandon the site or become insolvent, and with-holds payment as leverage to get the work done (or to retain funds for it to be done by others). The architect (if doing observation and contract administration) loses hair and sleep trying to get the project back on track, and the client holds the architect responsible for the contractor’s work – or lack of it, whilst the contractor thinks the architect has been biased in under-certifying payments due. If the architect is not involved in the construction phase, then the client and contractor will both take the position that the drawings and specification were inadequate and the cause of all these problems. When the client consults their lawyers, the death spiral has firmly taken hold, and the prospect of an amicable resolution fades.

BIM Risks

Some members have expressed an interest in understanding the risks associated with BIM – Building Information Modelling. I don’t claim any particular BIM expertise but the following is drawn from my personal experience on medium to large commercial projects, and is therefore by no means exhaustive.

Before having anything to do with BIM, members should acquaint themselves with the New Zealand BIM Handbook https://www.biminnz.co.nz/nz-bim-handbook and its appendices.

These are very useful documents and contain more detail than the NZCIC guidelines. More detailed information is also in the international standard ISO 19650. These documents are a reminder that BIM is much more than a fancy parametric CAD model, and that during the life of a project there are many ways in which ‘information’ might be used.

One of the key aspects of BIM is that the work you do is generally used by and relied upon by numerous downstream parties (e.g. construction, operation) so it’s very important that what you input into a BIM model is correct and so, before you even start, you need good internal modelling standards, templates, and systems. Also make any limitations about the model/information clear. A good BIM model is much more valuable than a simple set of drawings and so you should charge appropriately for this.

There are various views of how you can protect your intellectual property rights but, assuming the use of an NZIA AAS, the licence to use the model is similar to the drawings and belongs to them. The IP also lies in how you model things and carry out Quality Assurance but this will largely remain within your team and not be passed on.

As the lead consultant the architect is often also looked upon to provide BIM Management Services. Only provide these if you are confident that you have, and can maintain, this skillset.

The following identifies some of the hazard and risk areas by typical workstage.

Project Establishment/Briefing

Request for Proposal (RFP)

- Dealing with poorly written RFPs. These can contain broad requirements like ‘a clash-free BIM model is to be provided to the contractor as part of the construction documentation’ or a have requirement to provide ‘a complete as-built BIM model to LOD 300’. These can be very onerous or impractical, and to manage this risk it is important to review the RFP documents looking for these requirements, seek clarification if possible, and respond clearly with what your proposal includes.

- If you are part of a consultant team bid then it’s worth doing a pre-contract BIM Execution Plan (BEP) so that everyone knows what they’re committing to and what is covered by the fee. BIM is typically highly collaborative and such a BEP clearly sets out what everyone is expected to deliver. This minimizes the risk of disagreements later and, if included in your bid, can make it clear what is in scope.

- Make sure that you identify and charge accordingly for managing the BIM process if you have that role. This will include the BIM manager’s time but can also include project related costs like a Common Data Environment (CDE) where the BIM model is hosted, and licences for BIM collaboration and model-checking software. This can all add up to a considerable sum.

- Ensure that proper protocols are in place (with all participants) to manage cyber security risks, and make sure you have the appropriate Cyber Liability insurance in place in case something goes wrong.

Briefing

- It is important to get a BIM brief that is signed off by the client. The NZ BIM Handbook Appendix E shows an example of such a brief. On more than one occasion we have had to assist the client with writing the brief. Confirm that the client understands what they are getting and that you can deliver it. Getting an agreed brief reduces the risk of the client coming back later with additional information requirements.

Design Stages

The primary risks for this stage of the project are those associated with inefficiencies, poor coordination, and tension with your consultants.

Working with a consultant team during the design stages

- The foundation for a good consultant team producing good BIM is a well-executed and monitored BEP which is led by the BIM Manager.

- The BEP makes it clear what is required at each workstage and where responsibility sits, so take the time to properly review and input into this document, and ensure it is agreed upon by all parties as soon as possible.

- It is important for future users that the project uses OpenBIM (i.e. a non-proprietary format). Revit is quite dominant with consultants, but ArchiCAD is popular with architects so ensure that consultants are committed to exchanging models in an open formation like IFC (International Foundation Class) rather than their preferred CAD programme.

- Make sure that your hardware can deal with the large file sizes that you will end up with. For example, curved pipes and ducts can make these very large.

- Carry out testing prior to the actual execution of exchanges and clash detection.

The Design Process

- To have a decent BIM model you should have an internal model-coordinator on your team. This is different to the BIM manager, which should be regarded as an independent role, even if you are providing those services.

- Focus on clashes that are appropriate to the workstage. For example large clashes are important to resolve at early design stages but don’t sweat the small stuff as this will be very time consuming.

- Be careful of letting the ‘CAD people’ be the only team members engaged in the process. A successful BIM project needs buy-in from all disciplines and levels, and good transparency to avoid silos developing.

Procurement

The main risks with this project stage are getting tenders/prices that don’t properly take account of the contractor’s BIM responsibilities, and have the potential to generate later claims.

It is very important that tenderers for the construction are aware of the following:

- The status of the model that they will be provided with, including the level of development of the various BIM Model components.

- Any limitations or qualifications about the model being provided.

- What the contractor will be required to do with the model and who will do this work. For example, who will be responsible for updating the model as a result of variations or shop drawings, and what LOD will be required?

- How will shop drawings be reviewed – drawings only or models only or both?

- Are as-builts required and what is the level of accuracy of these?

- Is any BIM reporting needed during the construction phase?

Tenderers should be required to submit a construction BEP to confirm that they properly understand and have included for all BIM aspects.

Construction/Handover/Operation

- Responsibility during the construction stage will rest largely with the main contractor and sub-contractors. There may be some risk to the architect if they have a role of updating the model and do this poorly.

- Like non-BIM projects there is also the obvious risk of variation claims arising from poorly executed design, coordination and documentation in the earlier stages.

- To enable a smooth handover from contractor to client/user, the defects liability period can be used for a ‘soft landing’. The BIM Manager is likely to have a role in monitoring this.

- There are likely to be fewer risks to the design team members during the building operation stage but it’s important to ensure that the client has the necessary skills and software to make proper use of the BIM model. This will reduce the risk of an operational failure and any possible resultant claim.

Summary

The best way to mitigate BIM risks is the usual combination of good communication, thoroughness, and quality assurance.

You need to think carefully about the fees necessary to do it properly.

Risk management issues

- The BIM model is dependent on multiple contributors and will be relied upon by others for future unknown decisions. How do you confine your liability to your input only? This is likely to require specific terms of engagement.

- If an “issue” arises out of the use of the BIM model, there is the potential that you may incur costs and resources regardless of the relevance of your contribution to it. How do you “ring-fence” or allocate the respective inputs by the various contributors or users?

- If there is some ambiguity or conflict between the BIM model and the other responsibilities you have under your engagement – or have described in your design/specification – which takes precedence?

- The definition of quality standards may require amendments to address the standardisation of BIM guidelines.

- Is there a “BIM protocol” which specifically deals liability and responsibility, order of precedence, and the resolution of conflict?

- There need to be protocols to trace work carried out in BIM and establish what occurred, who did what to whom and when, and to establish causation in the event a dispute arises.

- What are the intellectual property rights and ownership issues? Who “owns” the BIM model and controls access and use? To what extent does it affect your copyright on design elements?

- Check that your professional indemnity insurance covers failures due to BIM design, and what additional provisions you may need to make. Your duty to disclose material facts to your insurer may require you to disclose that BIM is implemented on a project.

- The operation of BIM on a project may inadvertently allow parties to access information which is otherwise confidential. Parties may consider restricting access to different areas of BIM.

Observation

Observation

Our website has several articles on “observation”. When claims are based on building failures, inevitably the role of observation comes under scrutiny. This article is the combination of thoughts from four NZACS Directors: Peter Marshall, Alec Couchman, Michael Davis, and Colin Orchiston.

Observation versus Contract Administration

The current standard forms of engagement and contract intermingle observation with contract administration, and whilst they are interdependent, they are also separate. This separation of roles is likely to increase, and the NZIA is actively involved in current MBIE consultations around establishing the contract administration role as a stand-alone.

If you are engaged for observation you can report on what you have observed, but the duty to administer the contract – including ruling on variations, certifying payments and completion – rests with the contract administrator.

A consequence of separating the roles might be that rectification needed as a result of the observation role cannot be enforced because the leverage obtainable by with-holding payments is at the discretion of the separate contract administrator.

The role of Observation by the Architect primarily arises out of the terms of engagement between the Principal and the Architect. The role of Contract Administration arises out of the (building) contract between the Principal and the Contractor. If a building contract provides for independent observation (as does NZIA SCC at 8.8 and NZS3910 at 6.4) then those terms will provide the scope and rights/obligations applicable. If the building contract does not provide for independent contract administration or observation, and/or is inconsistent with the architect’s terms of engagement, the scope and terms will need to be agreed elsewhere, failing which they will be uncertain.

In a larger practice, the roles of designer, contract administrator and observation can be parcelled out to different staff, and the bigger projects suggest repetition of some site activities; when the same person does all three roles, the familiarity with the project suggests that critical aspects for observation should be known.

Partial Observation is a high-risk option

Any hint that the terms of engagement include observation will lead to assertions that building failures are the result of the architect failing to correct the work at the time it was done.

This makes the provision of “partial services” or “limited observation” or “site attendance on request only” or some fixed (eg weekly or monthly) site visit frequency a risky proposition which should be resisted. These arrangements may remove or diminish your control over the sufficiency of your observation, and yet you may still be held responsible for the full weight of “proper” observation.

It would be nice to just say “don’t do it” but the reality in the market is that it is necessary to view it as an unwelcome option that requires careful risk management.

- Who is to say what you could or should have seen when you went on site?

- Or whether you were on site sufficiently?

- Or for the right reasons or at a critical point in time?

Our website has several articles on “Partial Services” and they are not the focus of this article, but it is difficult to defend an allegation of inadequate observation on the basis that only “limited” oversight was intended, or was possible.

One of the early WHRS claims considered the defence offered by a Building Inspector that he was over-worked and the available resources provided by his employer meant that he could not adequately carry out the level of inspection necessary: unsurprisingly the Court took the view that the regulatory duties were not diminished because of management failures by the provider!

Against that background, there has to be a very thorough defence to justify why an architect engaged for observation did not – or could not –instruct rectification of observably defective work.

The Observation role should be whole-hearted, with attendances as and when required, with fair and commensurate fees, and with scope and fees sufficiently flexible to deal with changes in the circumstances of the project.

How much is “enough”?

The Project Architect should assess the level of observation and the frequency of site visits at time of agreeing the terms of engagement. It is (possibly) more important to set out what you won’t do, than to say what you will do; and essential to provide for changes to reflect the changing circumstances of the project. The architect’s risks are compounded if the level of observation as agreed in the original terms of engagement does not correlate with the level of observation later required or sought.

In smaller projects this may arise because the client removes observation and contract administration from the architect’s scope during the procurement process.

In larger projects it would not be unusual for the architect to be appointed early in the process and then later a project manager arrives who then appoints and instructs the consultants; the architect is removed from the contractor procurement process; contract administration is undertaken by others; the architect’s role is limited to clarifying the documentation and restricted site access for monthly reporting; the consultants remain responsible for observation but do not have the power to obtain rectification; yet on completion the funding agencies look to the architect to certify completion.

Engineers have a structured approach to determining the level of observation and frequency, but it does not take into account the issues we face as architects carrying out observation. It is not really about how often one visits the site, but whether the site visits capture the critical issues: that suggests that the project architect should be keeping an eye on the site progress, identifying what issues are likely to be critical if not performed as required, and planning site visits around those issues. Subject to ongoing review, an initial assessment might be on the following basis:

OL1 Intermittent Site Visits: small & simple projects fortnightly visit

OL2 Periodic Site Visits: medium complexity & size weekly visit

OL3 Regular Site Visits: larger or more complex twice weekly visit

OL4 Constant Site Visits: major complexity and scale every second day

This may or may not suit the project, the potential risk, or the fee, and is complicated by:

- Construction activity varying over the duration of the project, from site mobilisation and excavation through to a myriad of trades finishing works.

- The skills and experience of the contractors and sub-contractors, which may require more observation to mitigate risk.

- Progress on site varying from programme or expectations.

- Sufficiency accuracy and reliability of design and as-built documentation, and the level of co-ordination between consultants, may lead to more on-site queries and site visits.

- Substitutions or redesign sought by contractors; client and/or project manager changes, demands, expectations; similarly, from incoming occupants/owners and their funders, and overlaps with fitout requirements.

- Critical technical and programme issues, specific design complexities, perhaps where the risk of non-compliance varies disproportionally in relation to cost, scale and complexity.

- The need to exhibit to the contractor and client that you are “on top of things”

- The number of site visits not reflecting the duration of the visit, eg 1 hour; 3 hours, etc.

There is also a “bell-curve” which is typical: for smaller projects especially, a lot of attendance is necessary at the start of the job while the builder is grappling with what is required (and the architect is gauging how much hand-holding or vigilance may be required); in the middle of the project when there is a lot of repetitive work the only reason to visit might be for the purpose of valuing a progress claim; at the closing stages monitoring of finishing items may be to the level necessary to keep the client happy.

Observation does not mean inspection, or supervision

Lawyers and the courts do not appear to recognize the fine hair-splitting implied in this statement, and lawyers seemingly make no distinction between undertaking one site visit a month as opposed to a permanent site presence when it comes to blame. But that doesn’t make the distinction incorrect. It suggests that we need to do more to communicate the distinction.

Supervision is the control and direction of the work; Observation is a review of the work done.

Observation of a typical installation versus every installation

We are judged against what is deemed to be the actions of a reasonable architect in those circumstances at that time.

If you observe a representative quantum of a particular aspect of work to confirm that it matches your documentation and make the assumption on reasonable grounds that the remainder of that work will be similar, those are the actions of a reasonable architect. If a client wants more than that they need a clerk of works, and even then there’s no guarantee of perfection.

It is reasonable – in absence of evidence to the contrary – that an Architect assume that the contractor is competent: if a typical item of work is acceptable, and there was nothing to suggest that the remainder of that type of work would be executed any differently, then those other instances of that work may be assumed to also be acceptable.

But if a window is leaking because of an obvious and observable fault, and the architect did not notice the poor installation when there was the opportunity and need to do so, then they will be dragged into the issue, regardless. To claim that inspecting one window is sufficient for all windows would be a weak defence if 90% of the windows subsequently leaked (even if the one window the architect did inspect was perfect).

If you review an item of construction in detail and it is aligned with the documentation and complies with NZBC you can accept it, but you cannot then step back and not carry out observation of those repeating elements. At the very least you would need to review the repeated elements to the extent necessary to conclude that they were consistent with the item reviewed in detail. If the review of several such items revealed a variation in installation quality, the conclusion would be that site quality control is lacking, and more follow-up is required.

The question is whether what was observed was representative of that part of the construction: inspecting a window “type A” may or may not inform about the installation of types B,C etc. If there are 100 similar items then a reasonable assessment has to be made whether to observe in detail 1,10, or any number of them to be satisfied that the work is being done as required. Were they installed by the same persons at a similar point in time? By skilled or unskilled staff? What quality controls were in place? What are the consequences of failure? Who is likely to respond – and how – in the event of failure? For marginally acceptable items, how does the installed item compare to independent benchmarks or to supplier’s requirements?

Be very wary of providing any sort of statement as to quality/completion/compliance

Your observation role is to report on whether the work done complies with the contract requirements; your reporting can only be on the basis of what you have seen, and what you can reasonably infer from what you have seen. Your reporting will be dependent on the conditions under which the observation took place: the weather, the available access, whether the item was complete or in progress, and what information was provided to you by those on site who directed the work. If your reporting is based on assumptions, make those assumptions known.

Your observation reports will be used for two purposes: to inform the contract administrator about the progress and compliance with the contract requirements, and to provide ammunition to those who want to pin liability on you for subsequent shortcomings.

Does the 10 year longstop still apply?

Not so long ago, in our Communique article “How long to keep records” we said

“The warm fuzzies induced by the 10 year longstop on liability under the Building Act have been under threat from cases brought to Court. So far, so good. But it would be unwise to biff out everything related to a project as soon as the longstop is reached”

Alas, in May 2021 the decision on the October 2020 hearing of BNZ Branch Properties Limited v Wellington City Council [2021] NZHC 1058 has made good on that threat. There may be the possibility of an Appeal, but currently, the position is that if (for example) the owner makes a claim on the contractor at 9 years and 364 days, that contractor would have another two years to seek a contribution from you as a “third party”.

The case arises out of the BNZ building on the waterfront in Wellington, which was damaged in the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake and later demolished.

In August 2019, BNZ sued the Wellington City Council for negligence in respect of granting the building consent, inspecting during construction, and issuing a CCC. A month later, Council sued the engineers, Beca, as a negligent third party, seeking a contribution in accordance with s17 of the Law Reform Act. Beca argued that it had provided its engineering services in March 2008, more than 10 years before Council filed its claim, and thus the claim was time-barred by s393(2) of the Building Act.

The issue before the court was not whether or not Beca was negligent, but whether – in consideration of the limitation issues – they were liable.

The Building Act s393(2) states

“….no relief may be granted in respect of civil proceedings relating to building work if those proceedings are brought against a person after 10 years or more from the date of the act or omission on which the proceedings are based.”

In simplistic terms, the understanding has been that you are not liable for your actions (as a building designer) beyond 10 years from the date on which your actions may have given rise to the alleged problems.

NZ case law has confirmed that in respect of primary claims between plaintiffs and defendants; but the position has not been so clear in relation to third party claims. This was a test case for that issue, with about $100 million at stake.

Beca argued that the use of the words “civil proceeding” in s393(2) of the Building Act was intended to include “every form of civil proceeding regardless of its source or makeup”.

The High Court, after a detailed consideration of the relationship between s393 of the Building Act, s17 of the Law Reform Act, and s34 of the Limitation Act 2010, held that the term “civil proceeding” in s393 of the Building Act refers only to a primary claim between a plaintiff and defendant, and does not include a claim for contribution.

Third party claims – such as the Council’s claim against Beca – must be initiated within a two-year period provided for in the Limitation Act 2010. This judgement establishes that so long as a claim is made on a party within the Building Act 10 year longstop, that party would then have two years in which to make a claim against third parties.

NZACS has previously suggested that the WHRS timelines justify keeping your documents 12 years, not just 10: such things may (almost) be in the past, but this new case reinstates that recommendation. Those “warm fuzzies” are now facing the reality of winter.